When Does Adolescent Egocentrism Begin and When Does It Appear Again

Chapter xx: Cognitive Development in Boyhood

- Describe Piaget'due south formal operational stage and the characteristics of formal operational idea

- Describe adolescent egocentrism

- Draw Data Processing inquiry on attention and memory

- Describe the developmental changes in language

- Describe the various types of boyish pedagogy

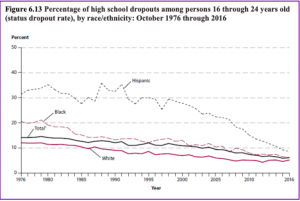

- Identify changes in high schoolhouse drop-out rates based on gender and ethnicity

Piaget's Formal Operational Stage During the formal operational stage, adolescents are able to understand abstract principles which have no concrete reference. They can at present contemplate such abstract constructs as beauty, love, liberty, and morality. The adolescent is no longer express by what tin be directly seen or heard. Additionally, while younger children solve problems through trial and error, adolescents demonstrate hypothetical-deductive reasoning, which is developing hypotheses based on what might logically occur. They are able to recall about all the possibilities in a situation beforehand, and and so test them systematically (Crain, 2005). Now they are able to engage in true scientific thinking.

Formal operational thinking also involves accepting hypothetical situations. Adolescents sympathise the concept of transitivity, which ways that a relationship between ii elements is carried over to other elements logically related to the first ii, such as if A<B and B<C, then A<C (Thomas, 1979). For example, when asked: If Maria is shorter than Alicia and Alicia is shorter than Caitlyn, who is the shortest? Adolescents are able to answer the question correctly

as they sympathize the transitivity involved.

Does everyone accomplish formal operations? According to Piaget, most people attain some degree of formal operational thinking but use formal operations primarily in the areas of their strongest interest (Crain, 2005). In fact, most adults do not regularly demonstrate formal operational idea, and in small villages and tribal communities, it is barely used at all. A possible caption is that an private's thinking has not been sufficiently challenged to demonstrate formal operational thought in all areas.

Adolescent Egocentrism: Once adolescents can sympathise abstract thoughts, they enter a world of hypothetical possibilities and demonstrate egocentrism or a heightened self-focus. The egocentricity comes from attributing unlimited power to their own thoughts (Crain, 2005). Piaget believed information technology was not until adolescents took on adult roles that they would be able to learn the limits to their own thoughts.

David Elkind (1967) expanded on the concept of Piaget's adolescent egocentricity. Elkind theorized that the physiological changes that occur during adolescence result in adolescents being primarily concerned with themselves. Additionally, since adolescents fail to differentiate between what others are thinking and their own thoughts, they believe that others are just as fascinated with their beliefs and appearance. This belief results in the boyish anticipating the reactions of others, and consequently amalgam an imaginary audience. "The imaginary audience is the adolescent's belief that those effectually them are as concerned and focused on their advent as they themselves are" (Schwartz, Maynard, & Uzelac, 2008, p. 441). Elkind thought that the imaginary audience contributed to the self-consciousness that occurs during early on adolescence. The desire for privacy and reluctance to share personal information may exist a further reaction to feeling nether constant ascertainment by others. Alternatively, recent inquiry has indicated that the imaginary audience is not imaginary. Specifically, adolescents and adults feel that they are often nether scrutiny by others, especially if they are active on social media (Yau & Reich, 2018).

Some other important consequence of boyish egocentrism is the personal fable or belief that one is unique, special, and invulnerable to harm. Elkind (1967) explains that because adolescents feel and so important to others (imaginary audience) they regard themselves and their feelings as being special and unique. Adolescents believe that just they accept experienced potent and various emotions, and therefore others could never empathise how they feel. This uniqueness in 1'southward emotional experiences reinforces the adolescent'due south belief of invulnerability, particularly to death. Adolescents will appoint in risky behaviors, such as drinking and driving or unprotected sex, and feel they will not suffer any negative consequences. Elkind believed that boyish egocentricity emerged in early on boyhood and declined in middle adolescence, notwithstanding, recent research has also identified egocentricity in tardily adolescence (Schwartz, et al., 2008).

Consequences of Formal Operational Thought: As adolescents are now able to retrieve abstractly and hypothetically, they showroom many new means of reflecting on information (Dolgin, 2011). For example, they demonstrate greater introspection or thinking about 1's thoughts and feelings. They brainstorm to imagine how the world could be which leads them to become idealistic or insisting upon high standards of behavior. Because of their idealism, they may become critical of others, especially adults in their life. Additionally, adolescents can demonstrate hypocrisy, or pretend to be what they are not. Since they are able to recognize what others expect of them, they will conform to those expectations for their emotions and beliefs seemingly hypocritical to themselves. Lastly, adolescents tin exhibit pseudostupidity. This is when they approach issues at a level that is too complex, and they neglect because the tasks are as well simple. Their new ability to consider alternatives is non completely nether command and they appear "stupid" when they are in fact bright, but not experienced.

Information Processing

Cognitive Control: As noted in earlier chapters, executive functions, such as attention, increases in working memory, and cerebral flexibility have been steadily improving since early childhood. Studies take found that executive role is very competent in adolescence. However, self-regulation, or the power to control impulses, may still fail. A failure in self-regulation is especially true when there is high stress or loftier need on mental functions (Luciano & Collins, 2012). While high stress or demand may tax even an adult'south cocky-regulatory abilities, neurological changes in the adolescent encephalon may make teens particularly decumbent to more risky decision making nether these conditions.

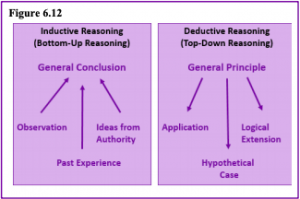

Anterior and Deductive Reasoning: Inductive reasoning emerges in childhood and occurs when specific observations, or specific comments from those in say-so, may exist used to draw full general conclusions. This is sometimes referred to as "bottom-upward-processing". However, in inductive reasoning, the veracity of the data that created the full general conclusion does not guarantee the accuracy of that conclusion. For instance, a child who has simply observed thunder on summertime days may conclude that it only thunders in the summertime. In contrast, deductive reasoning emerges in adolescence and refers to reasoning that starts with some overarching principle and based on this proposes specific conclusions. This is sometimes referred to as "top-downwardly-processing". Deductive reasoning guarantees a truthful conclusion if the premises on which it is based are accurate.

Figure half-dozen.12

Intuitive versus Analytic Thinking: Cognitive psychologists often refer to intuitive and analytic thought as the Dual-Process Model; the notion that humans take 2 distinct networks for processing information (Albert & Steinberg, 2011). Intuitive thought is automatic, unconscious, and fast (Kahneman, 2011), and it is more experiential and emotional. In dissimilarity, analytic thought is deliberate, witting, and rational. While these systems collaborate, they are distinct (Kuhn, 2013). Intuitive thought is easier and more unremarkably used in everyday life. It is as well more than commonly used by children and teens than by adults (Klaczynski, 2001). The quickness of adolescent thought, along with the maturation of the limbic system, may brand teens more than prone to emotional intuitive thinking than adults.

Education

In early adolescence, the transition from elementary school to heart school can be difficult for many students, both academically and socially. Crosnoe and Benner (2015) found that some students became disengaged and alienated during this transition which resulted in negative longterm consequences in academic operation and mental health. This may be because middle schoolhouse teachers are seen as less supportive than simple schoolhouse teachers (Brass, McKellar, Northward, & Ryan, 2019). Similarly, the transition to high school can be difficult. For example, high schools are larger, more bureaucratic, less personal, and there are less opportunities for teachers to get to know their students (Eccles & Roeser, 2016).

Peers: Certainly, the beliefs and expectations about academic success supported by an boyish's family unit play a significant role in the student's achievement and school engagement. However, research has also focused on the importance of peers in an boyish's school experience. Specifically, having friends who are high-achieving, academically motivated and engaged promotes motivation and date in the boyish, while those whose friends are unmotivated, disengaged, and depression achieving promotes the same feelings (Shin & Ryan, 2014; Vaillancourt, Paiva, Véronneau, & Dishion, 2019).

Gender: Crosnoe and Benner (2015) found that female person students earn better grades, endeavor harder, and are more intrinsically motivated than male students. Further, Duchesne, Larose, and Feng (2019) described how female students were more than oriented toward skill mastery, used a variety of learning strategies, and persevered more than males. Still, more than females showroom worries and anxiety nigh schoolhouse, including feeling that they must delight teachers and parents. These worries can heighten their try simply pb to fears of disappointing others. In contrast, males are more confident and practice not value developed feedback regarding their academic performance (Brass et al., 2019). At that place is a subset of female person students who identify with sexualized gender stereotypes (SGS), however, and they tend to underperform academically. These female students endorse the beliefs that "girls" should exist sexy and not smart. Nelson and Brown (2019) found that female students who support SGS, reported less desire to chief skills and concepts, were more skeptical of the usefulness of an education, and downplayed their intelligence.

Life of a high school student: On average, high school teens spend approximately 7 hours each weekday and one.1 hours each day on the weekend on educational activities. This includes attention classes, participating in extracurricular activities (excluding sports), and doing homework (Office of Adolescent Health, 2018). Loftier school males and females spend nigh the same amount of time in class, doing homework, eating and drinking, and working. However, they practise spend their time outside of these activities in different ways.

- High school males. On boilerplate, loftier schoolhouse males spend about one more 60 minutes per day on media and communications activities than females on both weekdays (two.9 vs. 1.viii hours) and weekend days (4.8 vs. 3.8 hours). They as well spend more time playing sports on both weekdays (0.9 vs. 0.v hours) and weekend days (1.2 vs. 0.v hours). On weekdays, high school males get an hour more sleep than females (9.2 vs. 8.ii hours, on average).

- High school females. On an boilerplate weekday, high school females spend more time than boys on both leisure activities (1.vii vs. 1.1 hours) and religious activities (0.1 vs. 0.0 hours). Loftier schoolhouse females also spend more fourth dimension on training on both weekdays and weekend days (1.1 vs. 0.7 hours, on average for both weekdays and weekend days).

High School Dropouts: The status dropout rate refers to the per centum of 16 to 24 year-olds who are non enrolled in schoolhouse and do not have high school credentials (either a diploma or an equivalency credential such as a General Educational Development [GED] certificate). The dropout rate is based on sample surveys of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population, which excludes persons in prisons, persons in the military, and other persons not living in households. The dropout rate among high school students has declined from a rate of 12% in 1990, to 6.i% in 2022 (U.Due south. Department of Education, 2018). The rate is lower for Whites than for Blacks, and the rates for both Whites and Blacks are lower than the rate for Hispanics. However, the gap betwixt Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics accept narrowed (run across Figure 6.13).

Effigy vi.thirteen

The dropout charge per unit for males in 1990 was 12%, where information technology stayed until 2000. Thereafter the rate has dropped to 7.ane% in 2016. The dropout charge per unit for females in 1990 was 12%, and it has dropped to 5.1% in 2022 (U.S. Department of Instruction, 2018).

Reasons for Dropping Out of School: Garcia et al. (2018) reviewed the research on why students dropped out of schoolhouse and identified several major obstacles to school completion. These included: Adolescents who resided in foster care or were part of the juvenile justice arrangement. In fact, being confined in a juvenile detention facility practically guaranteed that a student would not complete school. Having a physical or mental health condition, or the need for special educational services, adversely affected schoolhouse completion. Being maltreated due to abuse or neglect and/or being homeless also contributed to dropping out of school. Additonally, boyish-specific factors, including race, ethnicity and age, besides every bit family-specific characteristics, such as poverty, single parenting, large family unit size, and stressful transitions, all contributed to an increased likelihood of dropping-out of school. Lastly, customs factors, such as dangerous neighborhoods, gang activity, and a lack of social services increased the number of school dropouts.

School Based Preparatory Experiences

According to the U. S. Department of Labor (2019), to perform at optimal levels in all education settings, all youth need to participate in educational programs grounded in standards, clear performance expectations and graduation exit options based upon meaningful, accurate, and relevant indicators of student learning and skills. These should include:

- Academic programs that are based on clear state standards

- Career and technical education programs that are based on professional and industry standards

- Curricular and program options based on universal design of school, work and communitybased learning experiences

- Learning environments that are small and safe, including extra supports such as tutoring, as necessary

- Supports from and by highly qualified staff

- Admission to an assessment system that includes multiple measures, and

- Graduation standards that include options.

Teenagers and Working

Many adolescents piece of work either summer jobs or during the schoolhouse twelvemonth. Belongings a job may offer teenagers actress funds, the opportunity to learn new skills, ideas nearly future careers, and perhaps the true value of money. All the same, there are numerous concerns almost teenagers working, especially during the school year. A long-standing concern is that that it "engenders precocious maturity of more adult-similar roles and trouble behaviors" (Staff, VanEseltine, Woolnough, Silverish, & Burrington, 2011, p. 150).

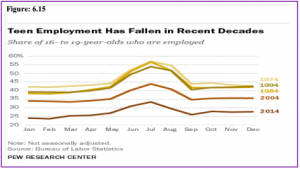

Several studies have found that working more than xx hours per calendar week can lead to declines in grades, a general disengagement from school (Staff, Schulenberg, & Bachman, 2010; Lee & Staff, 2007; Marsh & Kleitman, 2005), an increment in substance corruption (Longest & Shanahan, 2007), engaging in before sexual behavior, and pregnancy (Staff et al., 2011). All the same, like many employee groups, teens have seen a driblet in the number of jobs. The summer jobs of previous generations accept been on a steady decline, according to the United states Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2016). See Figure half-dozen.xv for recent trends.

Figure 6.15

Teenage Drivers Driving gives teens a sense of liberty and independence from their parents. Information technology tin also complimentary upward time for parents every bit they are not shuttling teens to and from schoolhouse, activities, or work. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) reports that in 2022 young drivers (fifteen to 20 year-olds) accounted for v.5% (xi.7 one thousand thousand) of the total number of drivers (214 1000000) in the US (National Center for Statistics and Analysis (NCSA), 2016).

Even so, most 9% of all drivers involved in fatal crashes that year were young drivers (NCSA, 2016), and co-ordinate to the National Middle for Wellness Statistics (2014), motor vehicle accidents are the leading cause of death for xv to 20 year-olds. "In all motorized jurisdictions around the world, immature, inexperienced drivers have much college crash rates than older, more than experienced drivers" (NCSA, 2016, p. 1). A teen's risk of an accident is especially high during the commencement months of receiving a license (CDC, 2018a). The charge per unit of fatal crashes is twice as high for young males as for young females (CDC, 2018a), although for both genders the rate was highest for the 15-20 years-onetime age group. For immature males, the rate for fatal crashes was approximately 46 per 100,000 drivers, compared to twenty per 100,000 drivers for immature females. The NHTSA (NCSA, 2016) reported that of the young drivers who were killed and who had alcohol in their system, 81% had a blood alcohol count past what was considered the legal limit. Fatal crashes involving alcohol use were higher among immature men than young women. The NHTSA besides found that teens were less likely to apply seat belt restraints if they were driving under the influence of alcohol, and that restraint utilise decreased equally the level of alcohol intoxication increased. Overall, teens have the lowest rate of seat belt utilize. In a 2022 CDC survey, only 59% of teens reported that they e'er wore a seat chugalug when riding as a passenger (CDC, 2018b). Crash information shows that almost half of teenage passengers who die in a automobile crash were not wearing a seat belt (Insurance Plant for Highway Safety, 2017).

In a AAA study of non-fatal, only moderate to severe motor vehicle accidents in 2014, more than than half involved young male drivers xvi to 19 years of age (Carney, McGehee, Harland, Weiss, & Raby, 2015). In 36% of rear-finish collisions, teen drivers were following cars too closely to be able to stop in time, and in single-vehicle accidents, driving besides fast for weather and road conditions was a cistron in 79% of crashes involving teens. Distraction was also a gene in nearly 60% of the accidents involving teen drivers. Fellow passengers, often also teenagers (84% of the fourth dimension), and cell phones were the top two sources of lark, respectively. This information suggested that having another teenager in the car increased the risk of an accident by 44% (Carney et al., 2015). According to the NHTSA, 10% of drivers aged 15 to 19 years involved in fatal crashes were reported to be distracted at the time of the crash; the highest figure for whatever historic period group (NCSA, 2016). Lark coupled with inexperience has been found to greatly increment the hazard of an accident (Klauer et al., 2014). Finally, despite all the public service announcements warning of the dangers of texting while driving, four out of 10 teens report having engaged in this inside the past 12 months (CDC, 2018b).

The NHTSA did observe that the number of accidents has been on a turn down since 2005. They attribute this to greater driver training, more social awareness to the challenges of driving for teenagers, and to changes in laws restricting the drinking age. The NHTSA estimates that the raising of the legal drinking historic period to 21 in all 50 states and the District of Columbia has saved 30,323 lives since 1975. The CDC also credits graduated commuter licenses (GDL) for reducing the number of accidents. While GDL programs vary widely, a comprehensive program has a long practice menstruum, requires greater parental participation, and limits newly licensed drivers from driving under sure loftier-chance conditions (CDC, 2018a).

References

Albert, D., & Steinberg, L. (2011). Adolescent judgment and conclusion making. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 211– 224.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th Edition). Washington, D. C.: Writer.

Arcelus, J., Mitchell, A. J., Wales, J., & Nielsen, Due south. (2011). Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 724-731.

Birkeland, M. S., Melkivik, O., Holsen, I., & Wold, B. (2012). Trajectories of global self-esteem during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 43-54.

Bosson, J. G., Vandello, J., & Buckner, C. (2019). The psychology of sex and gender. Grand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Brass, N., McKellar, North, E., & Ryan, A. (2019). Early adolescents' aligning at school: A fresh look at grade and gender differences. Journal of Early on Adolescence, 39(v), 689-716.

Dark-brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. K. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 74–103). New York, NY: Wiley.

Carney, C., McGehee, D., Harland, K., Weiss, Yard., & Raby, M. (2015, March). Using naturalistic driving data to appraise the prevalence of ecology factors and commuter behaviors in teen driver crashes. AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. Retrieved from https://www.aaafoundation.org/sites/default/files/2015TeenCrashCausationReport.pdf

Carroll, J. L. (2016). Sexuality at present: Embracing diversity (fifth ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Caspi, A., Lynam, D., Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. A. (1993). Unraveling girls' delinquency: Biological, dispositional, and contextual contributions to adolescent misbehavior. Developmental Psychology, 29(1), 19-30.

Center for Disease Control. (2004). Trends in the prevalence of sexual behaviors, 1991-2003. Bethesda, Physician: Writer.

Center for Disease Control. (2016). Birth rates (live births) per 1,000 females aged fifteen–19 years, by race and Hispanic ethnicity, select years. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/virtually/nativity-rates-chart-2000-2011-text.htm

Centers for Affliction Command. (2018a). Teen drivers: Go the facts. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/motorvehiclesafety/teen_drivers/teendrivers_factsheet.html

Centers for Illness Control. (2018b). Trends in the behaviors that contribute to unintentional injury: National Youth Risk Behavioral Survey. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/2017_unintentional_injury_trend_yrbs.pdf

Chein, J., Albert, D., O'Brien, Fifty., Uckert, Chiliad., & Steinberg, L. (2011). Peers increase adolescent take chances taking by enhancing action in the brain'southward reward circuitry. Developmental Science, xiv(2), F1-F10. doi: ten.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01035.x

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Soensens, B., & Van Petegem, S. (2013). Autonomy in family unit decision making for Chinese adolescents: Disentangling the dual meaning of autonomy. Periodical of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 1184- 1209.

Connolly, J., Craig, W., Goldberg, A., & Pepler, D. (2004). Mixed-gender groups, dating, and romantic relationships in early adolescence. Periodical of Research on Boyhood, fourteen, 185-207.

Connolly, J., Furman, Due west., & Konarski, R. (2000). The function of peers in the emergence of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence. Child Development, 71, 1395–1408.

Costigan, C. L., Cauce, A. Thousand., & Etchinson, One thousand. (2007). Changes in African American mother-daughter relationships during adolescence: Conflict, autonomy, and warmth. In B. J. R. Leadbeater & N. Way (Eds.), Urban girls revisited: Building strengths (pp. 177-201). New York NY: New York University Printing.

Côtè, J. Due east. (2006). Emerging machismo every bit an institutionalized moratorium: Risks and benefits to identity formation. In J. J. Arnett & J. T. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of historic period in the 21st century, (pp. 85-116). Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association Press.

Crain, W. (2005). Theories of development concepts and applications (5th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson.

Crooks, K. L., & Baur, Thousand. (2007). Our sexuality (tenth ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Crosnoe, R., & Benner, A. D. (2015). Children at schoolhouse. In Grand. H. Bornstein, T. Leventhal, & R. One thousand. Lerner (Eds.). Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Ecological settings and processes (pp. 268-304). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

De Wit, D. J., Karioja, G., Rye, B. J., & Shain, Grand. (2011). Perceptions of failing classmate and teacher support post-obit the transition to high school: Potential correlates of increasing student mental wellness difficulties. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 556-572.

Dishion, T. J., & Tipsord, J. M. (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Almanac Review of Psychology, 62, 189–214.

Dobbs, D. (2012). Cute brains. National Geographic, 220(iv), 36. Dolgin, K. Thou. (2011). The adolescent: Development, relationships, and civilization (13th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Duchesne, Southward., Larose, Due south., & Feng, B. (2019). Achievement goals and engagement with academic work in early on loftier school: Does seeking assist from teachers affair? Journal of Early on Boyhood, 39(2), 222-252.

Dudovitz, R.N., Chung, P.J., Elliott, G.N., Davies, S.L., Tortolero, South,… Baumler, Eastward. (2015). Relationship of historic period for course and pubertal phase to early initiation of substance use. Preventing Chronic Disease, 12, 150234. doi:10.5888/pcd12.150234.

Eccles, J. Southward., & Rosner, R. W. (2015). School and community influences on human development. In M. H. Bornstein & Thousand. East. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental scientific discipline (7th ed.). NY: Psychology Press.

Elkind, D. (1967). Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Evolution, 38, 1025-1034.

Euling, S. Y., Herman-Giddens, Yard.E., Lee, P.A., Selevan, South. G., Juul, A., Sorensen, T. I., Dunkel, L., Himes, J.H., Teilmann, G., & Swan, S.H. (2008). Examination of Usa puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics, 121, S172-91. doi: x.1542/peds.2007-1813D.

Eveleth, P. & Tanner, J. (1990). Worldwide variation in human growth (2nd edition). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Furman, W., & Shaffer, Fifty. (2003). The office of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 3–22). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Garcia, A. R., Metraux, S., Chen, C., Park, J., Culhane, D., & Furstenberg, F. (2018). Patterns of multisystem service employ and school dropout amidst seventh-, eighth-, and ninth-form students. Journal of Early on Adolescence, 38(8), 1041-1073.

Giedd, J. Northward. (2015). The amazing teen brain. Scientific American, 312(6), 32-37. Goodman, Chiliad. (2006). Acne and acne scarring: The instance for active and early on intervention. Commonwealth of australia Family Physicians, 35, 503- 504.

Graber, J. A. (2013). Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior, 64, 262-289.

Grotevant, H. (1987). Toward a process model of identity formation. Journal of Boyish Research, 2, 203-222

Harter, Due south. (2006). The self. In Due north. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3 Social, emotional, and personality evolution (sixth ed., pp. 505-570). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Harter, South. (2012). Emerging cocky-processes during childhood and adolescence. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney, (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 680-715). New York: Guilford.

Hihara, Due south., Umemura, T., & Sigimura, K. (2019). Because the negatively formed identity: Relationships between negative identity and problematic psychosocial behavior. Journal of Adolescence, 70, 24-32.

Hudson, J. I., Hiripi, E., Pope, H. Thou., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61(3), 348-358.

Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. (2017). Fatality facts: Teenagers 2016. Retrieved from http://www.iihs.org/iihs/topics/t/teenagers/fatalityfacts/teenagersExternal

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and tiresome. New York NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kim-Spoon, J., Longo, G.S., & McCullough, Grand.E. (2012). Parent-boyish relationship quality equally moderator for the influences of parents' religiousness on adolescents' religiousness and adjustment. Journal or Youth & Adolescence, 41 (12), 1576-1578.

King'south College London. (2019). Genetic report revelas metabolic origins of anorexia. Retrieved from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/07/190715164655.htm

Klaczynski, P. (2001). Analytic and heuristic processing influences on boyish reasoning and determination-making. Kid Development, 72 (3), 844-861.

Klauer, S. G., Gun, F., Simons-Morton, B. G., Ouimet, M. C., Lee, S. E., & Dingus, T. A. (2014). Distracted driving a adventure of route crashes among novice and experienced drivers. New England Journal of Medicine, 370, 54-59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204142

Kuhn, D. (2013). Reasoning. In. P.D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology. (Vol. 1, pp. 744-764). New York NY: Oxford Academy Press.

Lee, J. C., & Staff, J. (2007). When work matters: The varying bear upon of piece of work intensity on high school dropout. Folklore of Pedagogy, fourscore(2), 158–178.

Longest, Yard. C., & Shanahan, Thousand. J. (2007). Adolescent work intensity and substance use: The mediational and moderational roles of parenting. Journal of Family and Marriage, 69(3), 703-720.

Luciano, One thousand., & Collins, P. F. (2012). Incentive motivation, cognitive control, and the adolescent brain: Is information technology fourth dimension for a paradigm shift. Kid Evolution Perspectives, half-dozen (iv), 394-399.

March of Dimes. (2012). Teenage pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/teenage-pregnancy.pdf

Marcia, J. (2010). Life transitions and stress in the context of psychosocial development. In T.W. Miller (Ed.), Handbook of stressful transitions across the lifespan (Part ane, pp. 19-34). New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media.

Marsh, H. W., & Kleitman, S. (2005). Consequences of employment during high school: Character edifice, subversion of academic goals, or a threshold? American Educational Research Journal, 42, 331–369.

McAdams, D. P. (2013). Self and Identity. In R. Biswas-Diener & Due east. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook serial: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from: nobaproject.com.

McClintock, G. & Herdt, G. (1996). Rethinking puberty: The development of sexual attraction. Electric current Directions in Psychological Scientific discipline, v, 178-183.

Meeus, W., Branje, South., & Overbeek, G. J. (2004). Parents and partners in criminal offense: A six-yr longitudinal written report on changes in supportive relationships and delinquency in adolescence and immature adulthood. Journal of Kid Psychology & Psychiatry, 45(vii), 1288-1298. doi:ten.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00312.x

Mendle, J., Harden, M. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2010). Development's tortoise and hare: Pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology, 46,1341–1353. doi:10.1037/a0020205

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2012). Peer relationships and depressive symptomatology in boys at puberty. Developmental Psychology, 48(ii), 429–435. doi: x.1037/a0026425

Miller, B. C., Benson, B., & Galbraith, K. A. (2001). Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy adventure: A research synthesis. Developmental Review, 21(1), i-38. doi:10.1006/drev.2000.0513

National Center for Wellness Statistics. (2014). Leading causes of expiry. Retrieved from: http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcaus10_us.html

National Eye for Statistics and Analysis. (2016, May). Immature drivers: 2022 data. (Traffic Condom Facts. Report No. DOT HS 812 278). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Retrieved from: http://wwwnrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/812278.pdf

National Eating Disorders Association. (2016). Wellness consequences of eating disorders. Retrieved from https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/health-consequences-eating-disorders

National Institutes of Mental Health. (2016). Eating disorders. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders/index.shtml

National Sleep Foundation. (2016). Teens and sleep. Retrieved from https://sleepfoundation.org/sleep topics/teens-and-sleep

Nelson, A., & Spears Brown, C. (2019). As well pretty for homework: Sexualized gender stereotypes predict academic attitudes for gener-typical early adolescent girls. Journal of Early Boyhood, 39(4), 603-617.

Office of Adolescent Health. (2018). A day in the life. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/facts-and-stats/twenty-four hours-in-thelife/index.html

Pew Enquiry Center. (2015). College-educated men taking their time becoming dads. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/06/19/higher-educated-men-take-their-time-becoming-dads/

Phinney, J. S. (1989). Stages of ethnic identity development in minority grouping adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 9, 34- 49.

Phinney, J. Southward. (1990). Indigenous identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 499-514. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.iii.499

Phinney, J. S. (2006). Ethnic identity exploration. In J. J. Arnett & J. Fifty. Tanner (Eds.) Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st Century. (pp. 117-134) Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Rawatlal, N., Kliewer, Westward., & Pillay, B. J. (2015). Boyish zipper, family performance and depressive symptoms. South African Periodical of Psychiatry, 21(3), lxxx-85. doi:10.7196/SAJP.8252

Rosenbaum, J. (2006). Reborn a virgin: Adolescents' retracting of virginity pledges and sexual histories. American Periodical of Public Health, 96(6), 1098-1103.

Ryan, A. M., Shim, S. S., & Makara, K. A. (2013). Changes in bookish adjustment and relational self-worth beyond the transition to centre schoolhouse. Periodical of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1372-1384.

Russell, Due south. T., Clarke, T. J., & Clary, J. (2009). Are teens "postal service-gay"? Contemporary adolescents' sexual identity labels. Journal of Youth and Boyhood, 38, 884–890.

Sadker, G. (2004). Gender disinterestedness in the classroom: The unfinished agenda. In 1000. Kimmel (Ed.), The gendered gild reader, 2nd edition. New York: Oxford University Printing.

Schwartz, P. D., Maynard, A. M., & Uzelac, S. Thou. (2008). Adolescent egocentrism: A contemporary view. Boyhood, 43, 441- 447.

Seifert, K. (2012). Educational psychology. Retrieved from http://cnx.org/content/col11302/1.2

Shin, H., & Ryan, A. M. (2014). Early adolescent friendships and academic adjustment: Examining selection and influence processes with longitudinal social network assay. Developmental Psychology, fifty(11), 2462-2472.

Shomaker, L. B., & Furman, Westward. (2009). Parent-adolescent relationship qualities, internal working models, and zipper styles as predictors of adolescents' interactions with friends. Journal or Social and Personal Relationships, 2, 579-603.

Sinclair, Due south., & Carlsson, R. (2013). What volition I be when I grow up? The impact of gender identity threat on adolescents' occupational preferences. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 465-474.

Smetana, J. G. (2011). Adolescents, families, and social development. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. Soller, B. (2014). Defenseless in a bad romance: Adolescent romantic relationships and mental wellness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(1), 56-72.

Staff, J., Schulenberg, J. Due east., & Bachman, J. Thou. (2010). Adolescent work intensity, schoolhouse performance, and academic date. Sociology of Education, 83, p. 183–200.

Staff, J., Van Eseltine, M., Woolnough, A., Silver, E., & Burrington, Fifty. (2011). Adolescent work experiences and family unit formation behavior. Periodical of Research on Adolescence, 22(one), 150-164. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00755.x

Steinberg, L., Icenogle, Chiliad., Shulman, Due east.P., et al. (2018). Around the world, adolescence is a time of heightened sensation seeking and immature self-regulation. Developmental Science, 21, e12532. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12532

Syed, M., & Azmitia, Chiliad. (2009). Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity during the college years. Journal of Enquiry on Adolescence, 19, 601-624. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00609.x

Syed, M., & Juang, L. P. (2014). Ethnic identity, identity coherence, and psychological functioning: Testing bones assumptions of the developmental model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, xx(2), 176-190. doi:10.1037/a0035330

Tartamella, 50., Herscher, East., Woolston, C. (2004). Generation extra large: Rescuing our children from the obesity epidemic. New York: Basic Books.

Taylor, J. & Gilligan, C., & Sullivan, A. (1995). Between voice and silence: Women and girls, race and relationship. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Thomas, R. M. (1979). Comparing theories of child development. Santa Barbara, CA: Wadsworth.

Troxel, W. Chiliad., Rodriquez, A., Seelam, R., Tucker, J. Shih, R., & D'Amico. (2019). Associations of longitudinal sleep trajectories with risky sexual behavior during late adolescence. Health Psychology. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=x.1037%2Fhea0000753

Umana-Taylor, A. (2003). Ethnic identity and self-esteem. Examining the roles of social context. Journal of Boyhood, 27, 139-146.

U.s. Census. (2012). 2000-2010 Intercensal estimates. Retrieved from http://www.demography.gov/popest/data/index.html

The states Department of Pedagogy. (2018). Trends in high school dropout and completion rates in the The states: 2018. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019117.pdf

United States Section of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2016). Employment projections. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_chart_001.htm

Usa Department of Labor, Office of Disability Employment Policy. (2019). Schoolhouse based prepatory experiences. Retrieved from: https://www.dol.gov/odep/categories/youth/school.htm

University of California at Los Angeles Medical Heart. (2000). Acne. Retrieved from http://www.mednet.ucla.edu

Vaillancourt, Yard. C., Paiva, A. O., Véronneau, Thousand., & Dishion, T. (2019). How do individual predispositions and family dynamics contribute to academic aligning through the center school years? The mediating part of friends' characteristics. Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(4), 576-602.

Wade, T. D., Keski‐Rahkonen, A., & Hudson, J. I. (2011). Epidemiology of eating disorders. Textbook of Psychiatric Epidemiology, 3rd Edition, 343-360.

Weintraub, K. (2016). Young and sleep deprived. Monitor on Psychology, 47(2), 46-l. Weir, K. (2015). Marijuana and the developing brain. Monitor on Psychology, 46(x), 49-52.

Weir, K. (2016). The risks of earlier puberty. Monitor on Psychology, 47(3), 41-44.

Yau, J. C., & Reich, S. M. (2018). "Information technology's only a lot of work": Adolescents' self-presentation norms and practices on Facebook and Instagram. Periodical of Research on Adolescence, 29(1), 196-209.

Attribution

Adjusted from Affiliate vi from Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective Second Edition past Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Akin 3.0 unported license.

douglaspethilkiled.blogspot.com

Source: https://uark.pressbooks.pub/hbse1/chapter/cognitive-development-in-adolescence_ch_20/

0 Response to "When Does Adolescent Egocentrism Begin and When Does It Appear Again"

Post a Comment